History

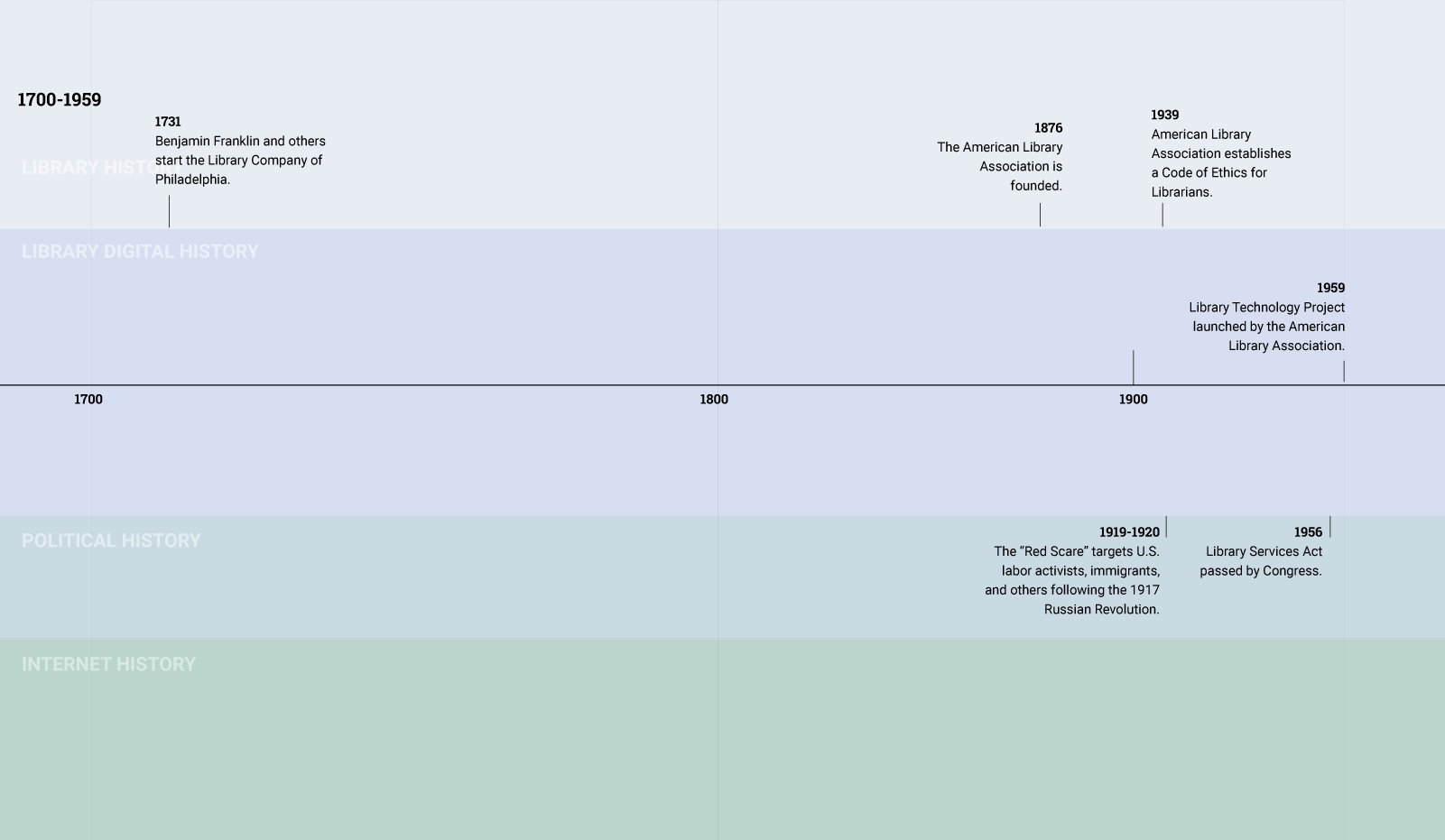

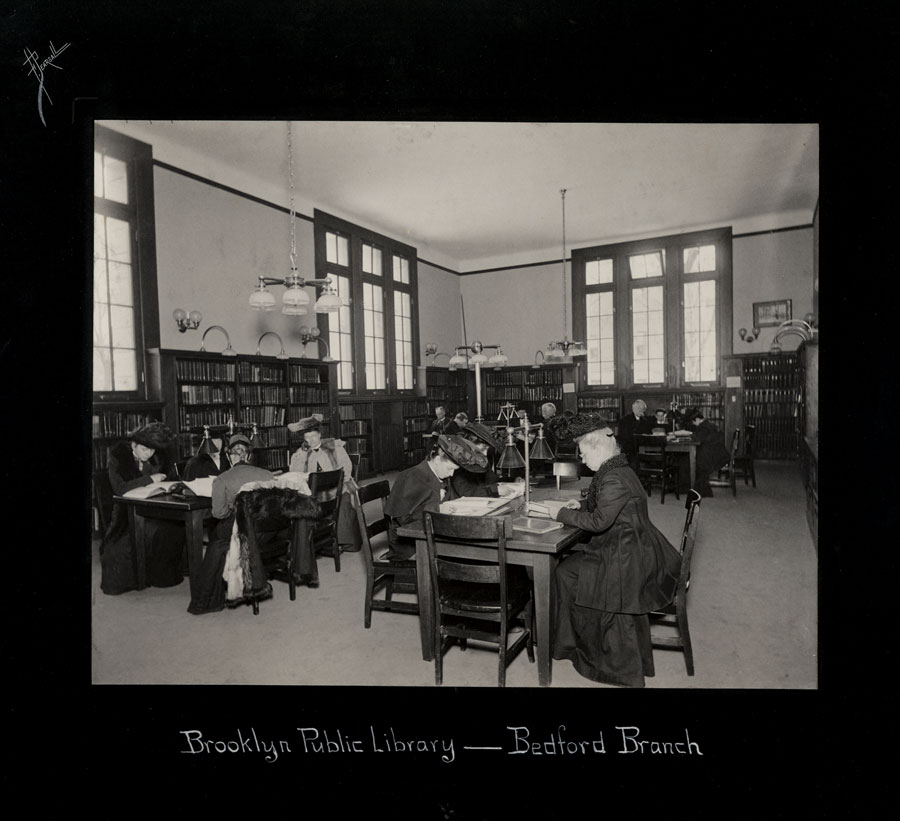

In the early 20th century, when the library profession was debating privacy and its relationship to free speech, information about patrons flowed in a relatively simple manner.

A patron communicated information about herself—her interests, beliefs, or values—in the process of borrowing a book. Book borrowing involved the library creating a paper record and storing it the library’s circulation records system.

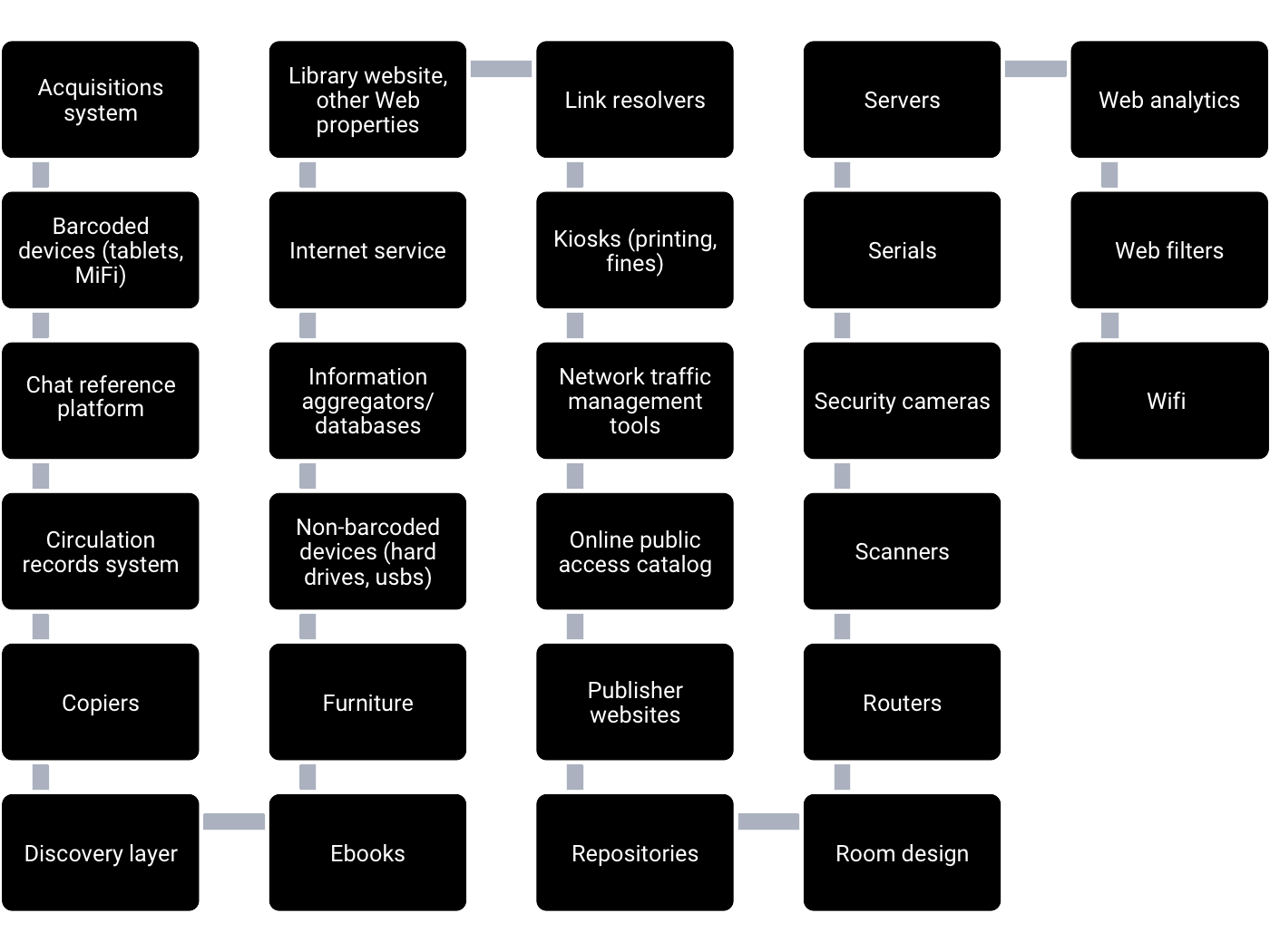

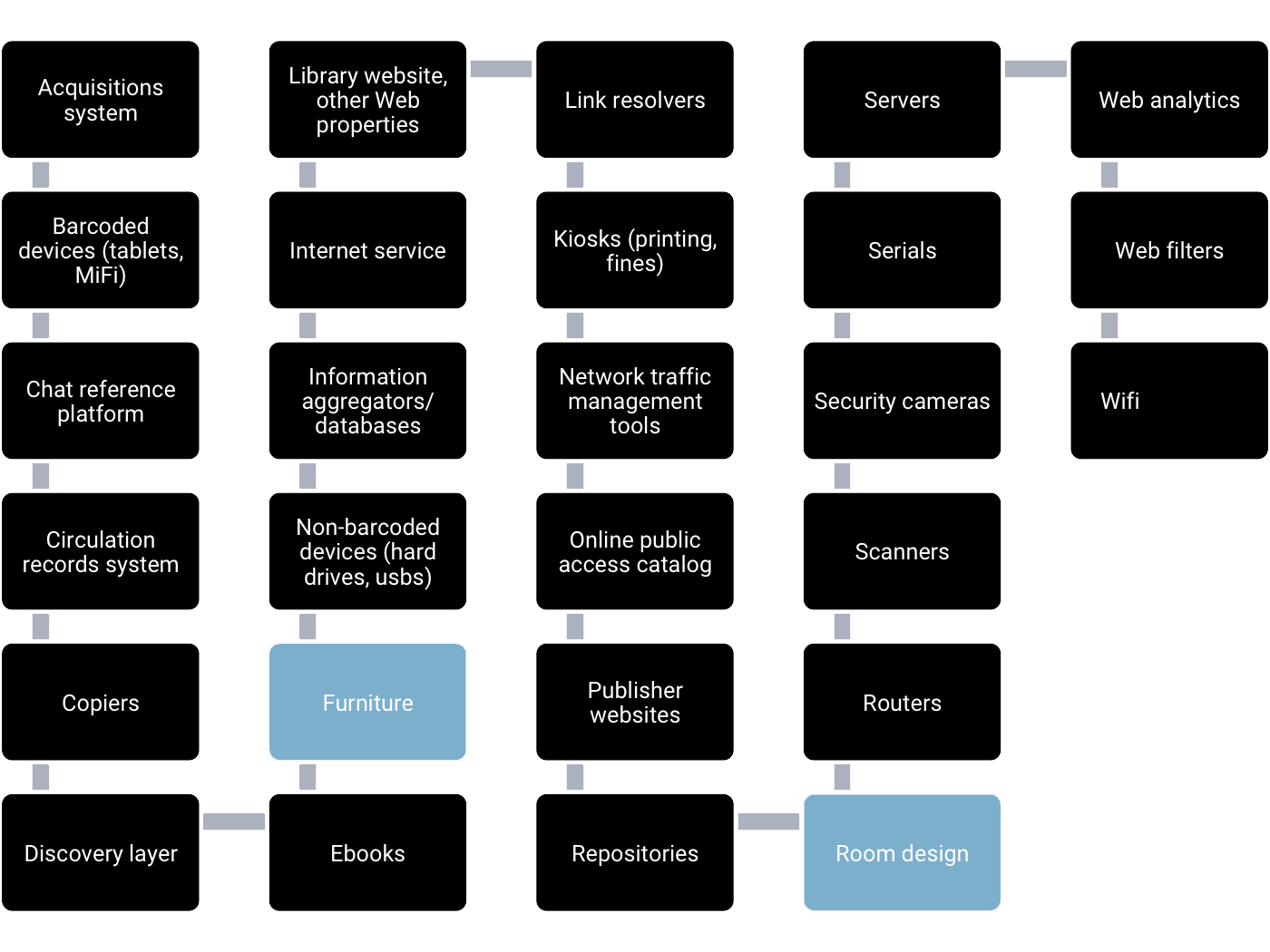

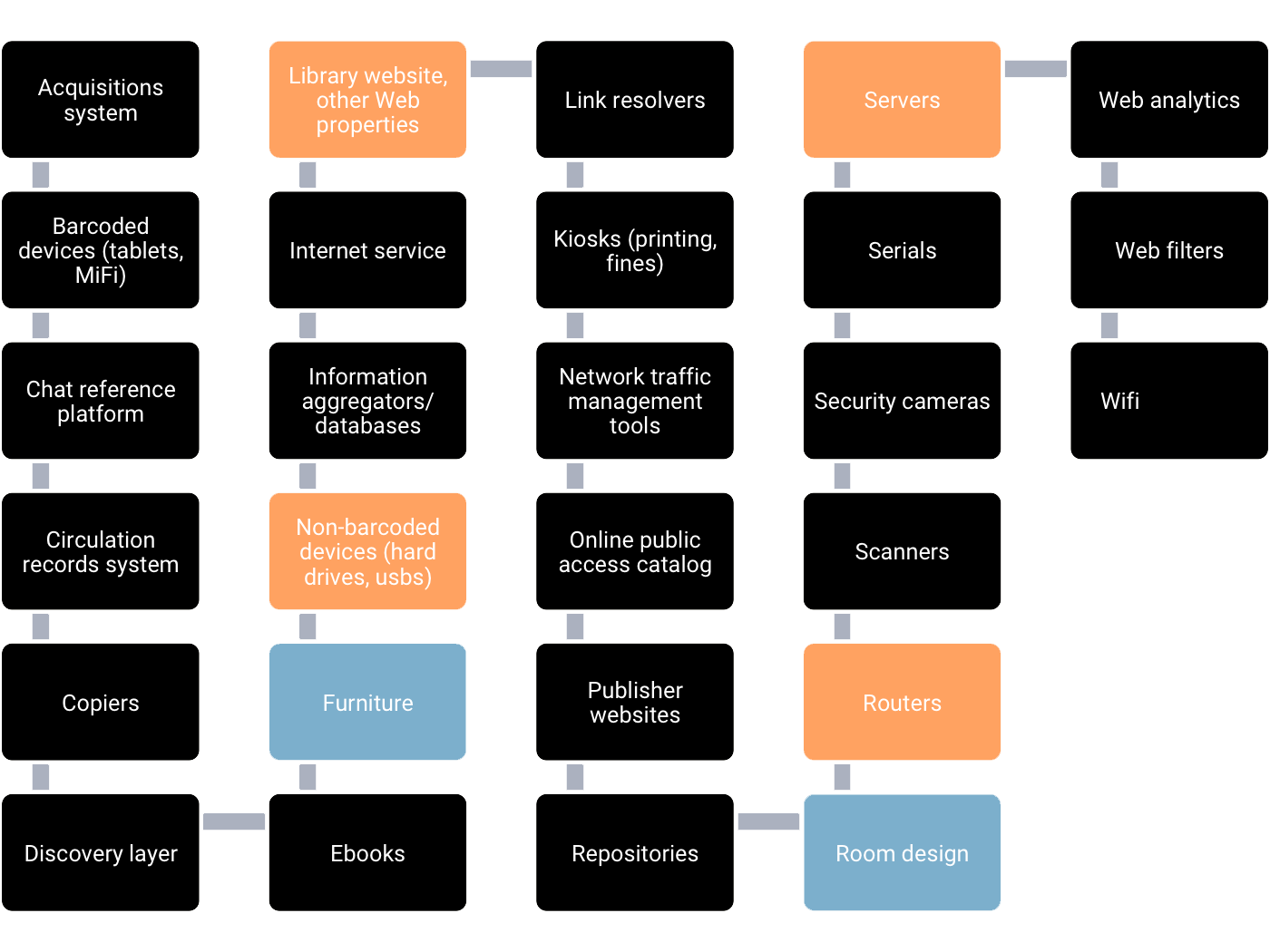

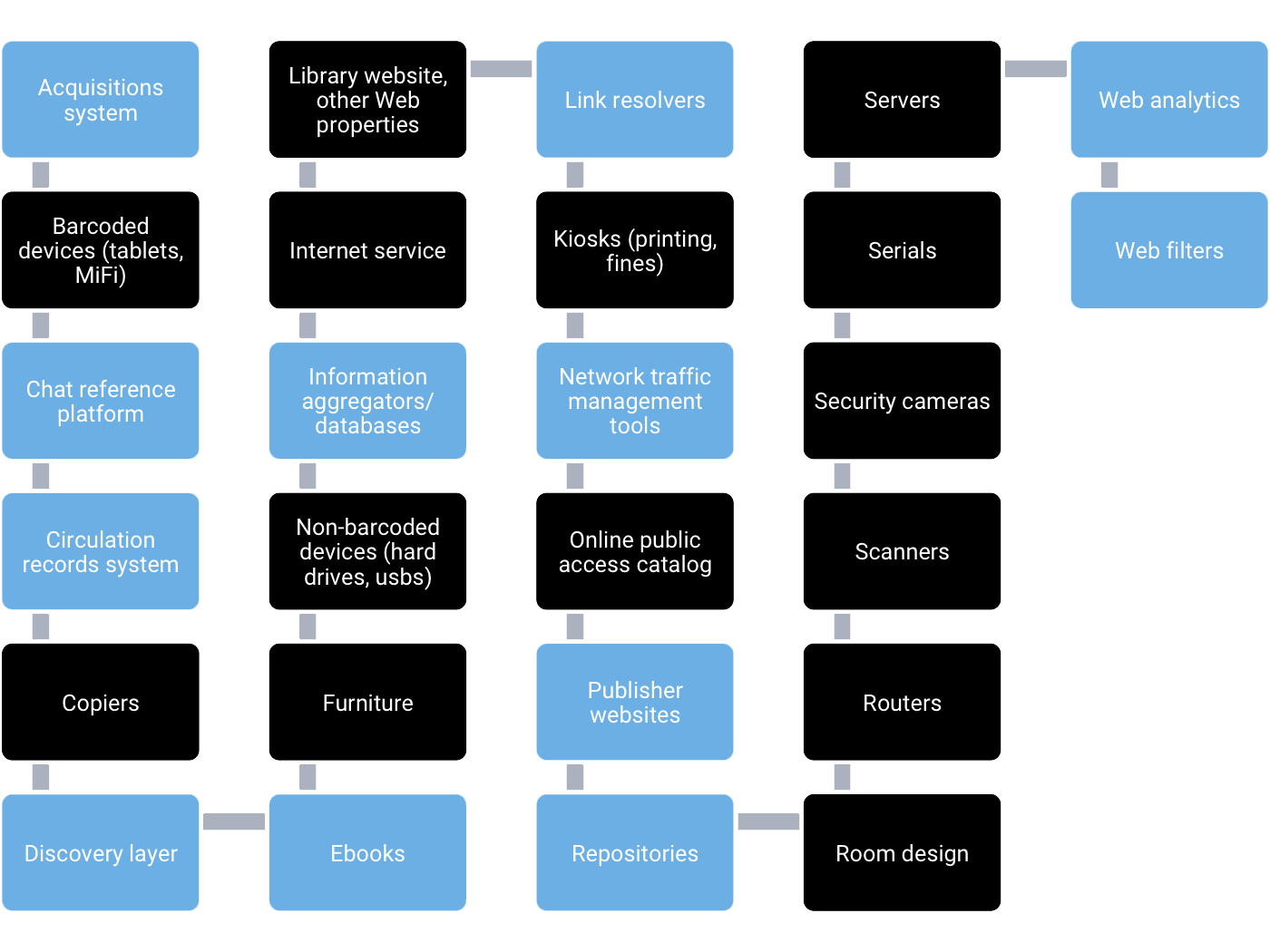

Over time, the library has evolved into a complex institution that is caught up in the flow of patron information in many different ways. Today, the library relies on numerous database-driven software applications to help it provide services to patrons.

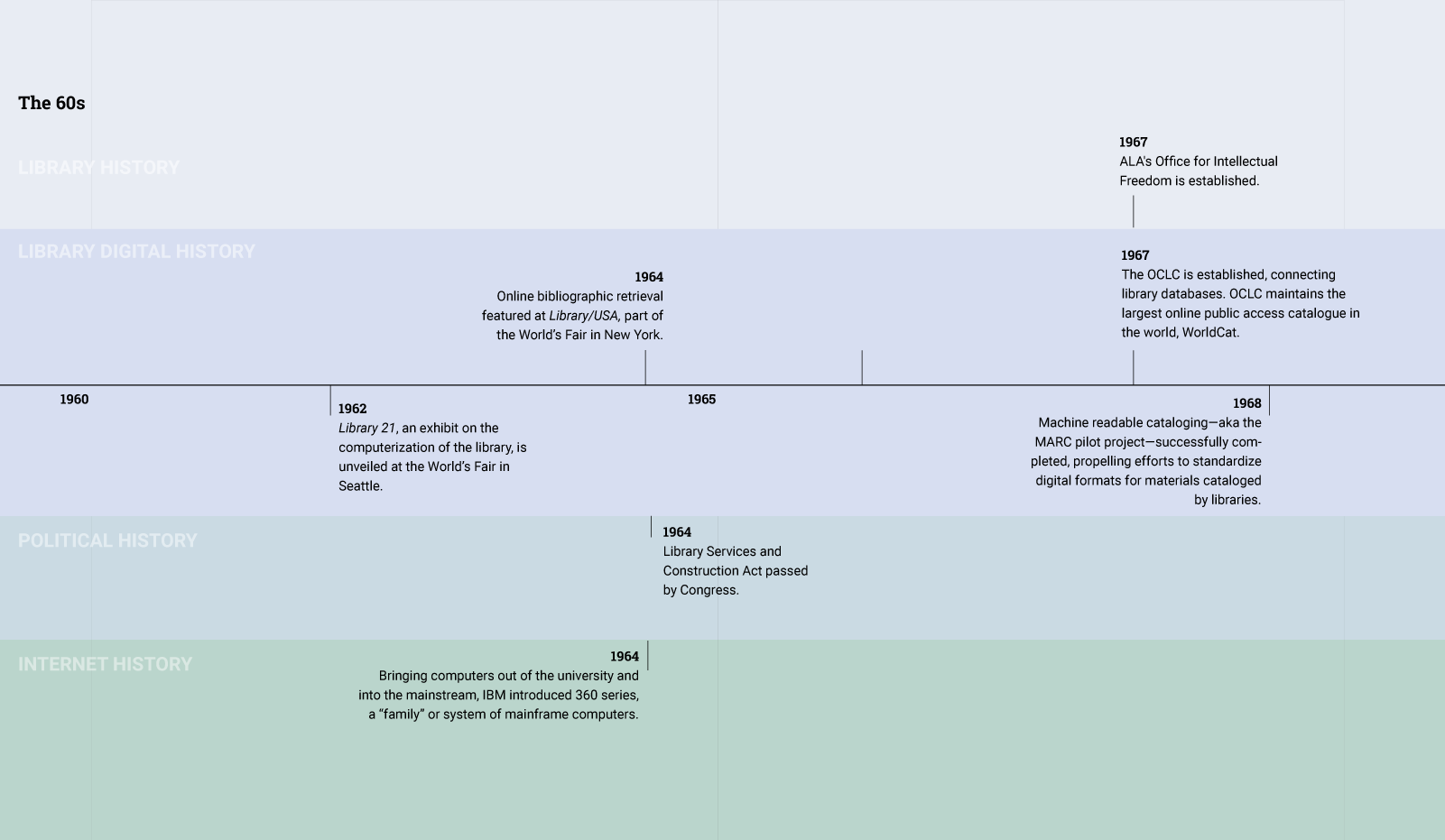

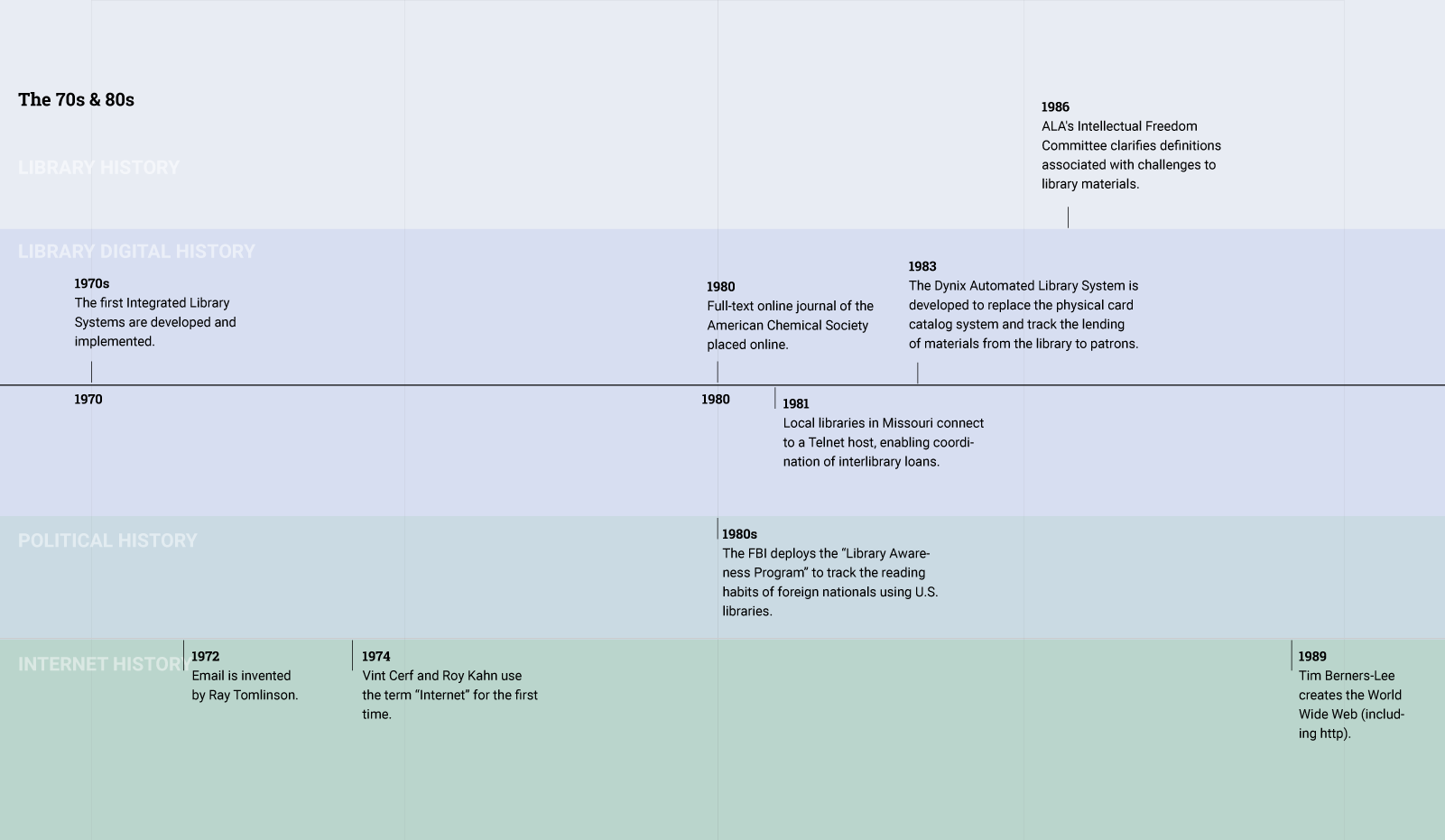

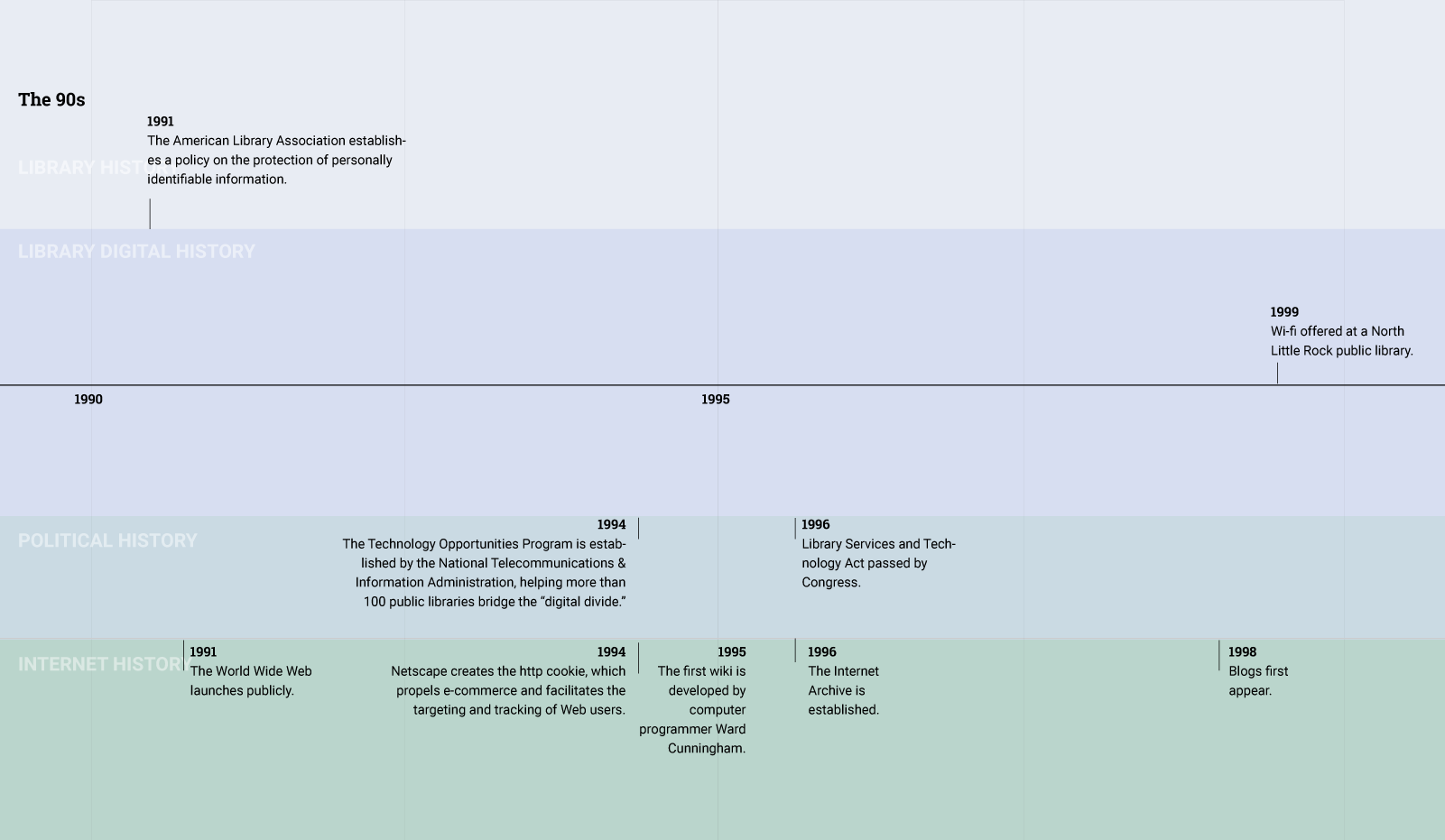

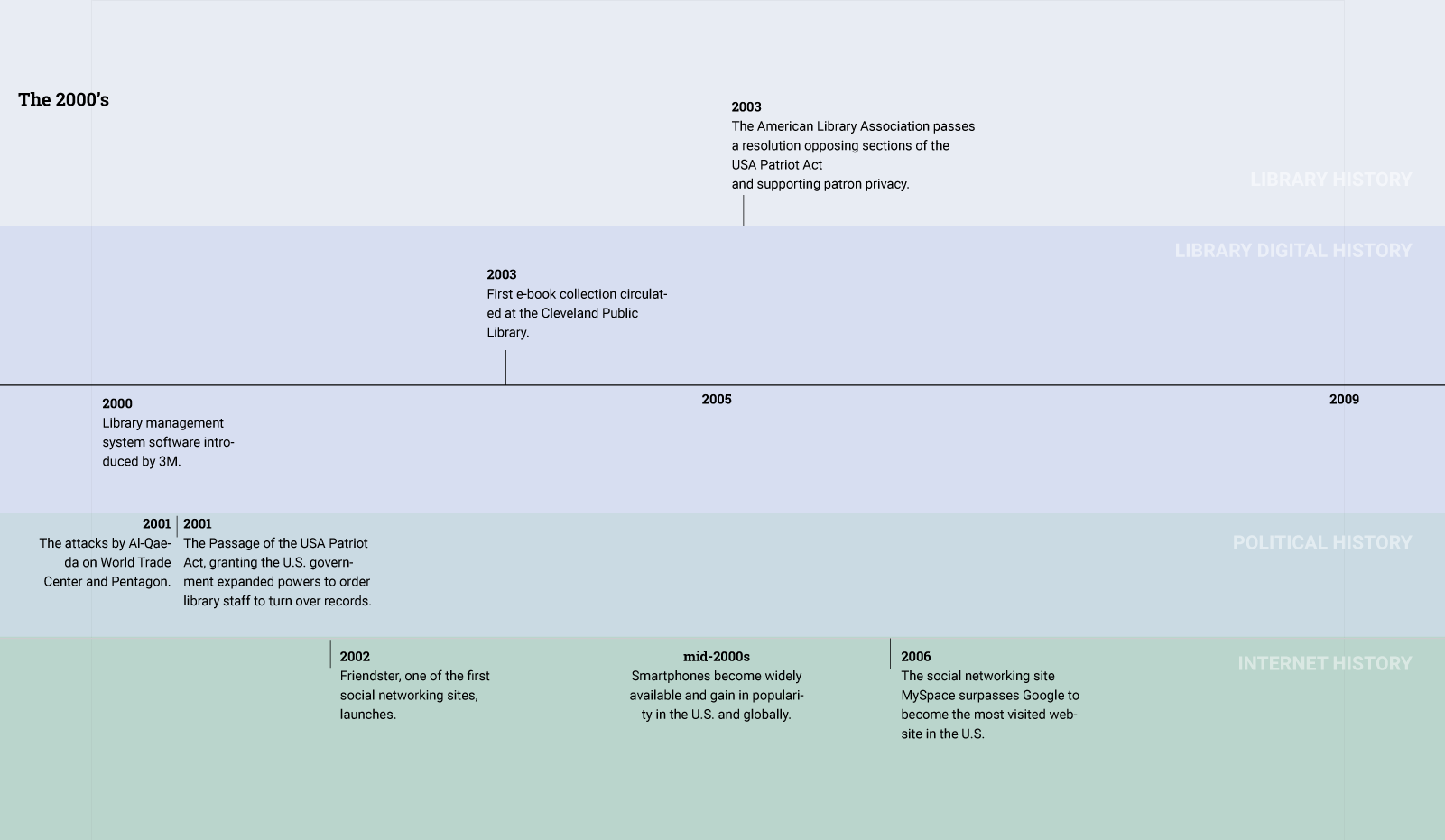

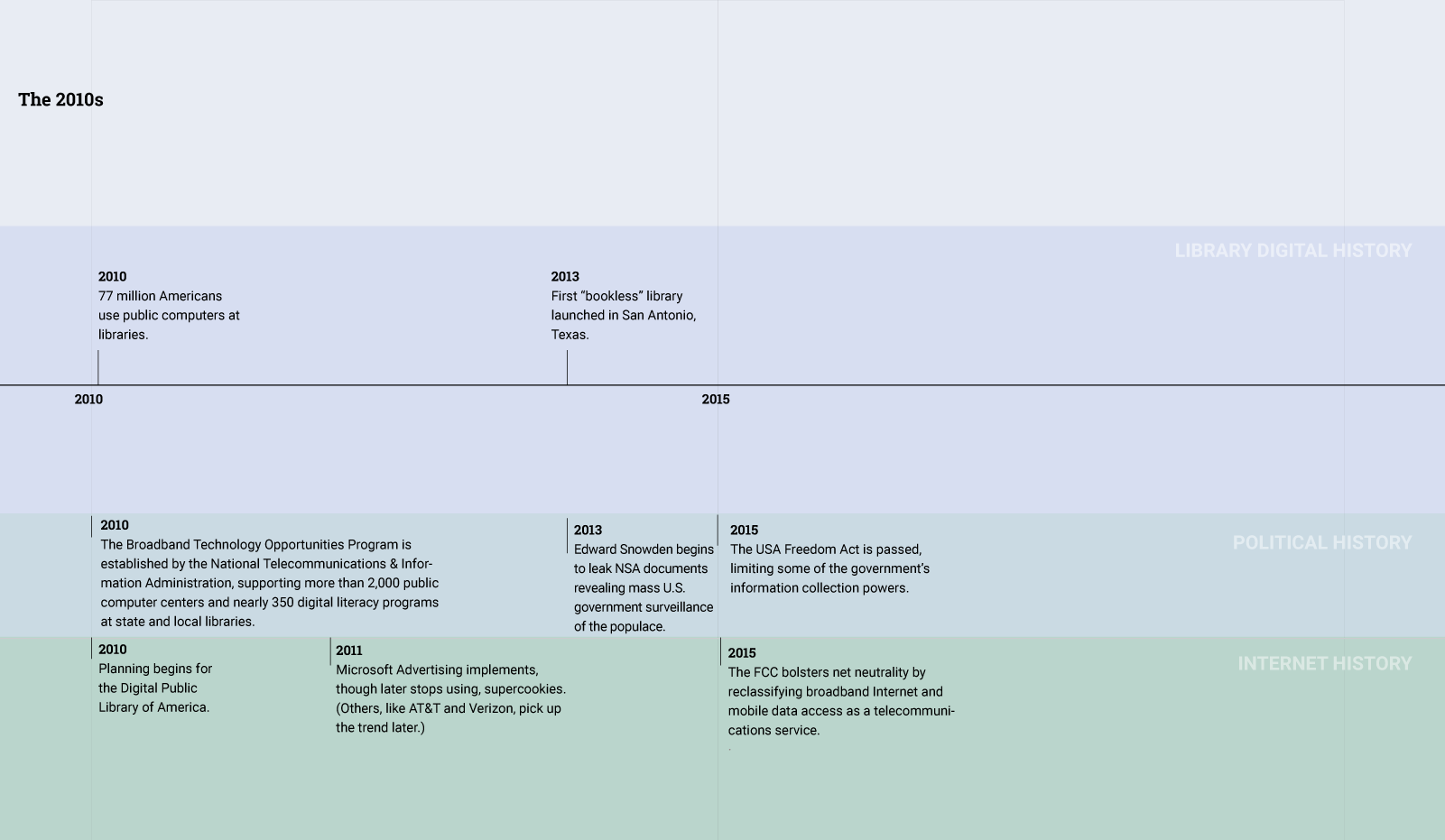

In the Sixties, at the same time that the library was modernizing, researchers were designing the proto-Internet. The next two decades saw the creation of protocols and standards that would lead to the creation of the Internet, email, and other networked communication tools. By the time that the commercial web took off in the Nineties, policymakers and library professionals were acutely aware of the transformative impact of the Internet and sought to eliminate "digital divide." As a result, libraries began transforming into places that not only lent books, but also provided public access to the Internet.

Today, libraries furnish communities with not only vital access to books, but also vital access to the Internet.These two trends—the digitization of the library’s catalog, circulation, and other information systems and the transformation of the library into a site for public Internet access—make the goal of patron privacy a challenging endeavor.

Challenges to Patron Privacy

The library offers a wide array of services to patrons that require them to share information about themselves to the library or to third parties that the library contracts with, including:

- Catalog searching

- Circulation transactions

- Collecting fines

- Access to journal and other periodical databases

- Email and online chat reference services

1.

2.

3.

4.

That’s not to say third-party policies determine everything, and the library has no power to shape and protect patron privacy. In reality, a complex set of factors determines how information flows about patrons.

Certainly, code—or the type of technology that a library implements—plays a role. For example, certain kinds of software encrypt or anonymize patron data to the extent that it’s difficult to determine what a particular patron is doing on the Internet.

Laws, whether at the local, state, or federal level, also shape the ways in which information about patrons will be dealt with. For example, some state laws, such as in the state of New York, dictate that library records must be kept confidential. Another law, the Children’s Internet Protection Act, influences network management at the library. If the library receives e-Rate funding, a federal subsidy program, it must install filtering software on its network that (ostensibly) prevents children from accessing harmful or obscene content on the Internet.

The library will have its own policies as well, including a privacy policy and computer and Internet use policies.

Finally, it’s worth mentioning that the practices, norms, and values of patrons and librarians as well will factor into how information flows about patrons. Some patrons might discover work-arounds to the library filtering system, for example, by using https by default. Library professionals may adopt certain practices, such as letting a patron use a guest pass, which means she does not affiliate her identity with a specific patron id number.

Shapers of Patron Data Flows

Privacy matters lie at the intersection of library policies; third party policies; local, state, and federal laws; social norms, values, and practices of library professionals and patrons; and technology itself.

Click on each part of the graphic above to learn more about these intersecting forces.

The library can pressure third parties about their terms of service or introduce technology that lets patrons obscure personal information as it travels through the library’s network. Third party providers can adopt secure solutions that make data leakage of patron information less likely.

Technologists can create privacy-protecting software that is effective and easy to use by people in the library - or in any setting.

Patrons as well as library professionals can participate in regulatory debates about privacy policies that affect whether and how the library provides patron data to legal authorities. And lawmakers can institute policies that support privacy and data literacy at the library.

Libraries can create policies, and update existing ones, to address the privacy of all types of data that flows through their servers. And patrons can affirm, question, and express concerns about these policies that affect their use of the library’s digital services.

People’s expectations of privacy are affected by legislation, media coverage of related events, community participation in digital platforms, the interfaces and policies of these platforms, and awareness of the flows of their data, among other factors. The library can play a role in shaping these expectations and educating people on what is possible to demand.

People’s expectations of privacy are affected by legislation, media coverage of related events, community participation in digital platforms, the interfaces and policies of these platforms, awareness of the flows of their data, among other factors. The library can play a role in shaping these expectations and educating people on what is possible to demand.

These ideas represent potential solutions, not necessarily actual ones… or at least not yet. As public conversation about privacy, data, and libraries evolves, the complexity of protecting patron privacy may subside. For now, we can identify both opportunities and challenges of patron data flows as they’ve changed over time.